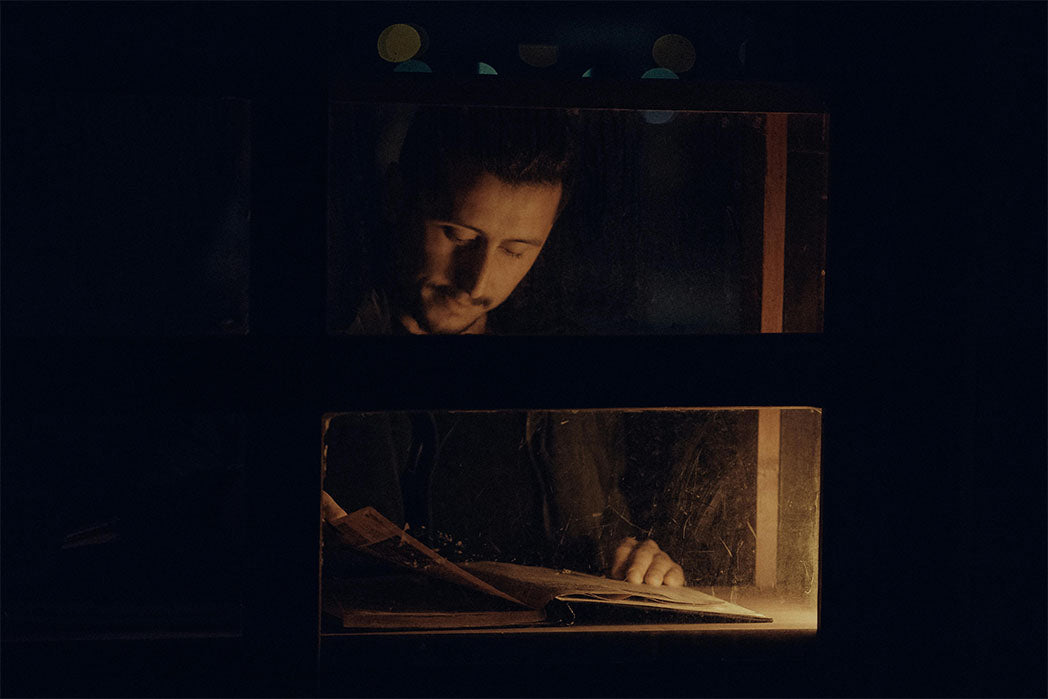

Did your parents ever tell you, “It’s not good for you to read in the dark. Turn the light on!”

You probably had no trouble seeing back then, and may have been confused at such comments.

As adults, we hear this often—that reading in the dark is bad for our eyes and may even damage them.

Is that true?

In this post, we examine the question and provide you with some tips on how to see better in dim lighting, regardless of your age.

Why Your Eyes Work Harder in Low Light

Our eyes have to adjust to different levels of lighting all the time. It seems automatic to us, but a lot is going on behind the scenes.

You can imagine three main players on the “team” of eyesight that are responsible for helping you to see under low-light conditions.

Pupil

This is that little black circle at the center of your eye, surrounded by the iris, which is the colored part. The pupil is an opening through which light passes, similar to the aperture in a camera. The iris is a muscle that adjusts the size of the pupil (opening) to reduce or increase the amount of light coming into the eye.

Under low-light conditions, the iris expands the pupil as much as possible. If you’ve ever been in the dark with a friend and then turned on a light while looking into their eyes, you would have seen the iris at work. The pupil would have been large at first, but then would have quickly diminished in size in response to the increase in light.

If you wait longer, though, you may find that your eyesight continues to improve. That’s because of the action of the cone cells.

Cone cells

Cone cells, or cones as they’re sometimes called, are one of two types of photoreceptor (light-sensitive) cells in the retina of the eye. To understand cones, we have to understand the retina.

The retina is the light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye. Images that come through the pupil are focused on the retina. It then converts those images to electric signals and sends them along the optic never to the brain. This is how we understand what it is that we’re seeing.

Cones are located in the center of the retina in the “macula” and are responsible for giving us our color vision. They also help us see fine details.

Humans have three types of cone cells:

- Red (long-wavelength)

- Green (medium-wavelength)

- Blue (short-wavelength)

These cone cells detect red, green, and blue colors. The other colors that we see, we experience as a mixture of these three colors.

Cone cells also contain light-sensitive chemicals called photopigments. When exposed to light, these chemicals react and convert light energy to electrical activity that our brains know how to interpret.

Cones work best in bright light, but they do adapt when the lights go out, becoming more sensitive so they can soak up as much light as possible. After about 5 to 10 minutes, they max out and let the rods do the work.

When you move from dark to light, however—such as when coming out of a movie into the bright sunlight—the cones are the ones that allow the eyes to adapt quickly.

Rod cells

Rod cells are also a type of photoreceptor cell, except they are concentrated in the outer areas of the retina rather than at the center. They are also 500 to 1,000 times more sensitive to light than cones and are more numerous. The retina has about six million cones, but about 120 million rods.

The rod cells also take in light and convert it to electrical signals sent to the brain. They are most responsible for black-and-white vision and are the team VIPs when it comes to low-light vision. They help us see better in the dark via several actions:

- They also contain a light-sensitive chemical called rhodopsin. In low-light conditions, the rods regenerate this chemical. That helps each rod cell to be about 100 to 1,000 times as sensitive as each cone cell.

- There are more rod cells than cone cells, and their sheer number helps improve night vision.

- Rods respond more slowly to light, meaning that they can collect light over longer periods. This increases your ability to see in low-light conditions and is called “dark adaptation

You can imagine the process in three separate steps. You go out at night to observe the stars and:

- Your pupil dilates within a few seconds, allowing more light in.

- Your cone cells adapt in about 5 to 10 minutes.

- Your rod cells continue to adapt, reaching their peak after an hour or two.

Reading in the Dark: As We Get Older, Our Eyes Don’t Adapt as Quickly

The somewhat complex process described above happens quickly and productively when the eyes are young and healthy. As we get older, however, things change.

First, the iris muscle may weaken, like the rest of the muscles in the body tend to do with age. That means it may take a little longer to adjust the pupil size in response to lighting changes.

Second, we tend to lose a significant number of rods as we get older. We maintain most of our cones, which is why we can still see well in bright light, but up to a third of our rods may no longer be present or function as they should.

As to why we lose these rods, scientists aren't sure. They have found that rods degenerate before cones and that a decline in their sensitivity is more prominent than a decline in cone sensitivity.

Reading in the Dark: The Rods Need More Time to Regenerate Rhodopsin

Third, the light-sensitive pigment or chemical in the rods regenerates more slowly in older eyes. So we have fewer rods, and the chemical in the ones we have left takes longer to regenerate.

Scientists tested this in a study. They measured dark adaptation in 94 adults ranging in age from the 20s to the 80s.

The results showed that during human aging, "there is a dramatic slowing in rod-mediated dark adaptation that can be attributed to a delayed rhodopsin generation." The time that it took the rods to regenerate rhodopsin decreased by 8.4 seconds per decade, while the amount of time to reach a baseline sensitivity increased by 2.76 minutes per decade.

The researchers concluded that these aging-related changes “may contribute to night vision problems…”

These changes tend to start around the age of 40. By the age of 65, you may notice that your eyes don’t adjust to darkness as well. You may also find that you need more light to see well, particularly when reading!

So Is Reading In the Dark Bad for Our Eyes?

We can say that reading in the dark will not damage your eyes. There is no scientific evidence that proves this. But eye strain is real, and it can cause soreness, fatigue, and other annoying symptoms that temporarily affect how well you can see.

First, reading in the dark requires your eyes to work harder. Now that you know how the process works, you can understand that if you read in dim lighting, you’re asking your eyes to do a lot of adjusting. That can lead to eyestrain, which can, in turn, cause dry eyes, discomfort, headaches, and fatigue. It can also make what you’re reading appear blurry, and may even lead to shoulder or neck pain.

If you have nearsightedness, astigmatism, or other eye conditions, the eye strain may be worse. You may also blink less when the lighting is dim, which could again lead to eyestrain and dry eyes.

Why put your eyes through that? Be kind and turn on the light!

What About Reading On a Screen?

If you’re reading on a computer, tablet, or cell phone in the dark, you may think that you’re covered because the screen itself emits light. Your eyes should be happy, right?

Not really. Reading a digital device in the dark can cause a couple of problems.

First, unless you adjust the lighting to reduce blue light, you could be messing with your sleep schedule. Blue light stimulates your body's "wake-up" response and can make it harder for you to fall asleep.

This is why it's not a good idea to read on a screen within an hour or two of bedtime unless you adjust the display accordingly. The process can stimulate hormones in your body that mess up your internal body clock, and sleep problems may result.

Second, reading on a device in the dark can cause eyestrain. That’s partly because most of us tend to blink less when staring at a screen. That can cause dry eyes, irritation, and blurred vision.

Third, you’re also asking your eyes to constantly adapt between the light on the screen and the surrounding darkness. They have to work harder to focus on the screen, then focus on the dark room around you, then focus on the screen again.

This can lead to a specific type of eyestrain called computer vision syndrome (CVS). CVS causes blurry vision, sore eyes, dry eyes, and headaches.

Reading in the Dark? Choose Print!

If you want to read at night, it’s much better for your eyes to read a print magazine or book.

The American Optometric Association (AOA) states that reading letters on a printed page is easier on your eyes, and doesn’t require the same amount of effort: “Often the letters on the computer or handheld device are not as precise or sharply defined, the level of contrast of the letters to the background is reduced, and the presence of glare and reflections on the screen may make viewing difficult.”

The AOA adds that the presence of even minor vision problems can significantly affect comfort and performance at a digital screen. If you have glasses or contact lenses, you may find that they don’t work as well at specific viewing distances.

“Some people tilt their heads at odd angles because their glasses aren’t designed for looking at a computer…” That can cause neck, shoulder, and back pain.

How to Reduce Eyestrain When Reading

If you want an optimal reading experience, follow these tips:

Go Natural When You Can: Natural light is absolutely the best thing for your eyes when reading. Whenever possible, set up your reading spot near a window or outside.

Choose Your Artificial Light Wisely: When you need artificial lighting, LED bulbs are your best friend. They give off that warm, cozy light that's way easier on your eyes than harsh fluorescent lighting.

Screen Time Solutions: If you're doing lots of screen reading, consider investing in blue light blocking lenses – they're a game-changer for reducing digital eye strain. Also, flip on that "night mode" setting to dial down the brightness and blue light. Your eyes will feel so much more relaxed.

Don't Force It: If you're over forty and finding yourself squinting or holding books at arm's length, don't push through the discomfort. Your eyes are telling you something, and it might be time to consider reading glasses or an updated prescription.

Match Your Environment: When reading on a device at night, try to make your room brightness similar to your screen. Reading a bright tablet in a completely dark room is like staring into a spotlight.

Remember to Blink: When we're focused on reading, we blink way less, which leaves our eyes feeling dry and tired. Conscious blinking helps to keep them lubricated.

Follow the 20-20-20 Rule: Every 20 minutes, take a 20-second break to look at something 20 feet away. It gives your focusing muscles a mini-vacation and prevents that tired, strained feeling.

Regular Eye Exam: Keep up with regular eye exams to make sure your glasses or contact prescription is up to date. Reading with an outdated prescription is like trying to run in shoes that don't fit.

How Color Temperature of Light Affects Your Reading Comfort

Color temperature isn't just some fancy photography term. It actually helps to give comfort to your eyes while reading. Warm lights (around 2700-3000K) are like wrapping your eyes in a cozy blanket, especially at night. They're soothing, gentle, and perfect for winding down with a good book.

On the flip side, cooler lights (5000-6500K) are like sharp, energizing, and great for when you need to focus and stay alert. Studies have shown that warmer color temperatures actually reduce eye strain in dim environments because they create less harsh contrast.

Matching your light's color temperature to the time of day is not just about comfort. This can boost both your mood and productivity.

How does prolonged exposure to poor lighting conditions affect eye health?

Longitudinal studies make it crystal clear that poor lighting conditions will push your retina to work overtime. Your retina isn't designed to handle this kind of stress day after day. When you force it to work in inadequate lighting, you are essentially fast-tracking vision problems.

A well-lit study space, reading area, or work environment can literally save your family's vision. Every single hour you spend in proper lighting instead of dim conditions is an investment in your long-term vision health. Make the switch to better lighting now, and your future self will thank you when you're not squinting through thick glasses or dealing with vision problems.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the notion that reading in the dark is inherently harmful to your eyes is not entirely accurate. While there's no direct evidence to suggest it causes permanent damage, the strain it puts on your eyes can lead to discomfort, fatigue, and other issues.

As we've explored, the process of adapting to low-light conditions involves intricate mechanisms within the eye, which may not function as efficiently as we age. Older adults may find it particularly challenging to adjust to darkness due to changes in pupil response and the slower regeneration of light-sensitive chemicals in the retina. Moreover, reading on digital screens in the dark presents its own set of challenges, including potential sleep disturbances and eyestrain.

To mitigate these issues, it's advisable to read in well-lit environments whenever possible and take regular breaks to rest your eyes. Choosing printed materials over digital screens can also offer a more comfortable reading experience. By understanding how our eyes function and implementing simple strategies to reduce strain, we can better preserve our vision and enjoy reading for years to come.

We hope you found this article helpful and if you'd to read more like this, have a look at our Eyecare category.